Hugo Simon

Hugo Simon, banker, activist, agriculturalist, art collector and patron of the arts, was one of the leading cultural figures in Berlin under the Weimar Republic. He was born on 1 September 1880 in Usch (Ujście), Posen, at that time still a province of Germany, today a part of Poland. His father was a teacher; and, on his mother’s side, he could trace his ancestry back to Meir Katzenellenbogen, chief rabbi of Padua in the sixteenth century and a legendary figure in European Jewish history. After a banking apprenticeship in Marburg, Hugo moved to Berlin around 1905, where he opened the banking house Carsch Simon & Co. in 1911 (which became Bett Simon & Co., after 1922).

In 1909, he married Gertrud Oswald, also from Posen, whose two sisters Olga and Cäcilie were wed, respectively, to journalist Alexander Bloch and politician Kurt Heinig, both active in socialist circles. Hugo and Gertrud Simon had two daughters, born in Berlin, Ursula in 1911 and Annette in 1917. The eldest married sculptor Wolf Demeter in 1929, and they had one son, Roger, born 1931.

During the First World War, Hugo Simon was active in the Bund Neues Vaterland, a pacifist organization that later became the German League of Human Rights. Among his fellow activists were lifelong friends Albert Einstein, Harry Graf Kessler and Stefan Zweig. This political engagement led to his appointment as Minister of Finance in the Prussian revolutionary cabinet of November 1918, a position he held until January 1919 when his party, the Independent Socialists (USPD), withdrew from the government.

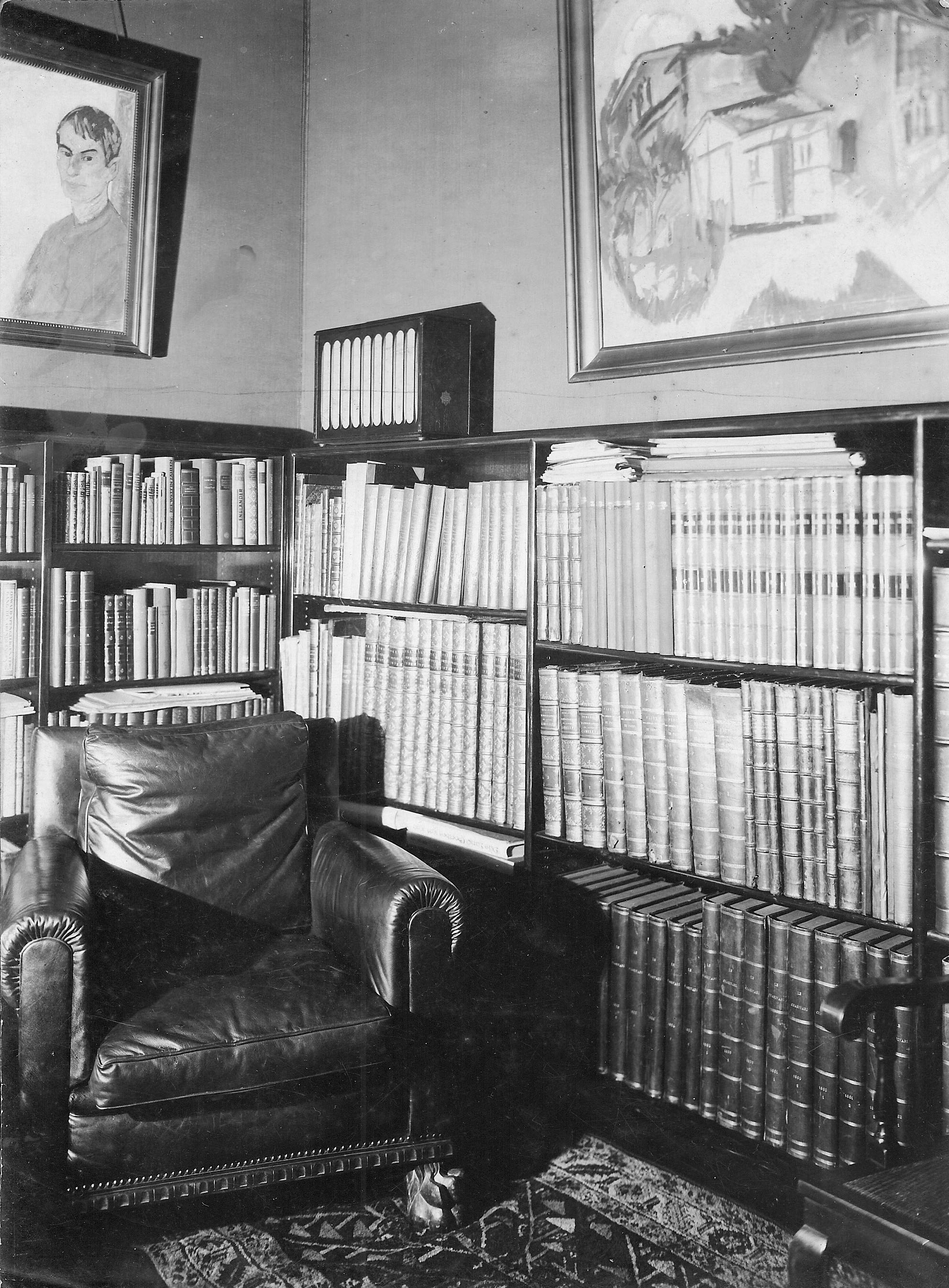

Thereafter, he turned his attention to art and culture. His private collection included works by Lyonel Feininger, George Grosz, Paul Klee, Oskar Kokoschka, Georg Kolbe, Wilhelm Lehmbruck, Aristide Maillol, Franz Marc, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Edvard Munch, Max Pechstein, Renée Sintenis, among many others. He was closely linked to the new National Gallery in Berlin, as a donor and member of its acquisitions committee. His villa in Berlin-Tiergarten was a well-known gathering place for artists and intellectuals. In 1919, he purchased the Schweizerhaus estate in Seelow, Oderbruch, where he developed a model agricultural enterprise over the 1920s.

Due to his political leanings and Jewish identity, Hugo Simon was targeted by the National-Socialist regime and forced into exile in March 1933. His assets in Germany were confiscated in October. He took up residence in Paris, where he established a brokerage firm and took part in the network supporting refugees arriving from Germany. He was active in anti-Nazi circles and one the main backers of the Pariser Tageszeitung, leading German-language newspaper for the exile community.

In October 1937, Hugo and Gertrud Simon were expelled from the German nationality and became stateless. When Paris was invaded in June 1940, they fled south, firstly to Montauban and then onward to Marseille. Their apartment in Paris was looted by the ERR and most of their art collection, books and furniture shipped back to Germany.

Like many exiles, the couple’s time in Marseille was dedicated to lining up the necessary visas to escape Vichy France; but Hugo Simon was unable to obtain an exit visa, since he was wanted by the Gestapo. After six months in limbo, they ultimately fled on foot over the Pyrenees into Spain, using false Czech passports issued under assumed names. From the port of Vigo, they were able to board a ship to Rio de Janeiro. Their daughters, son-in-law and grandson joined them in Brazil, soon thereafter, traveling with false French papers and under assumed names, as well.

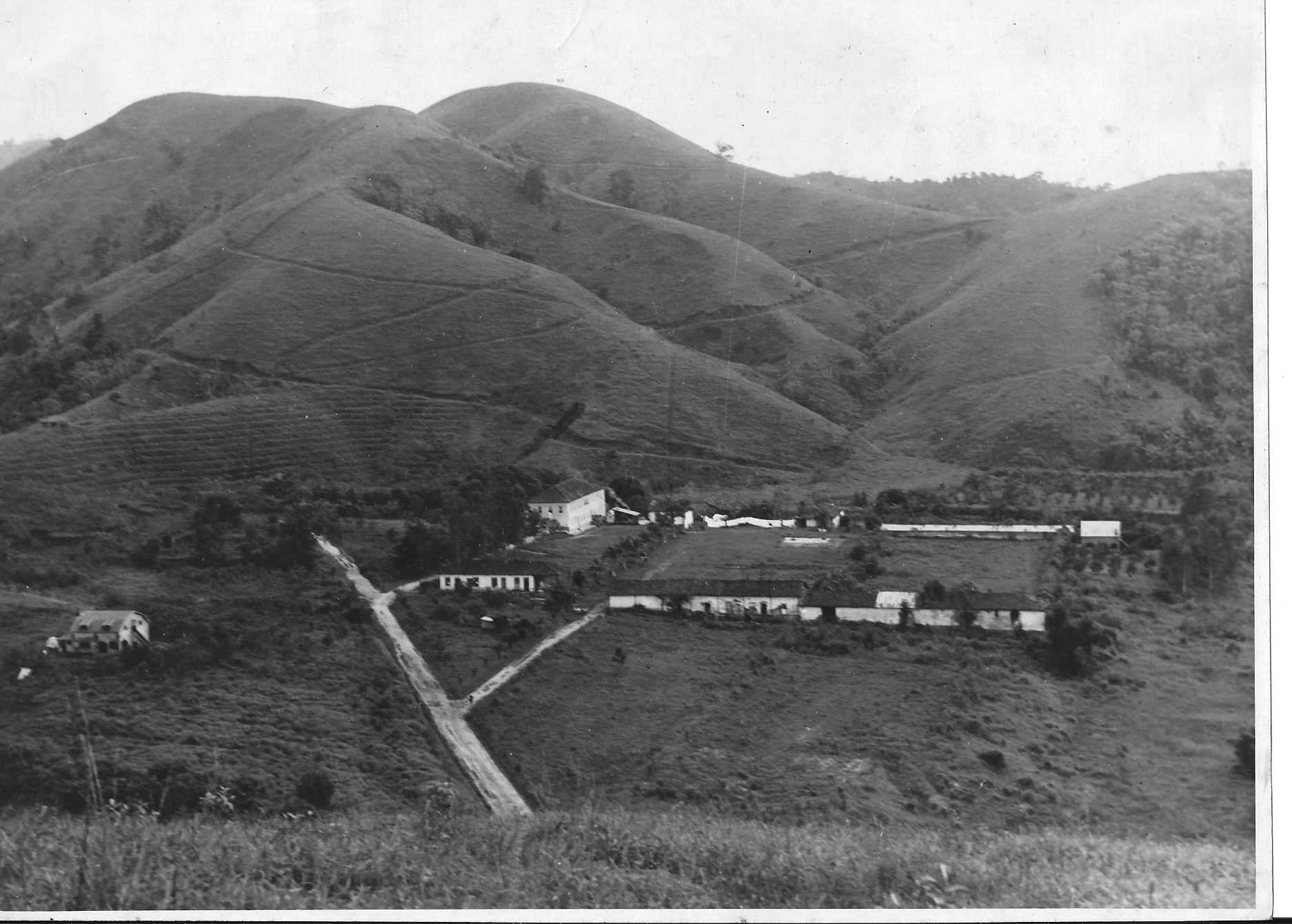

Upon arrival in Brazil, in February 1941, Hugo and Gertrud Simon were initially sheltered by the Catholic Monastery of Saint Benedict. In Rio de Janeiro, they reencountered old friends who had travelled the same route of exile, including Stefan Zweig and journalist Ernst Feder. After only a few months, Hugo received an official order to leave Brazil, expelled under the Vargas government’s secret directives for keeping out so-called ‘undesirable’ foreigners. Without valid papers, there was no chance of emigrating to another country, so the couple opted to go into hiding. They initially moved to Penedo – three hours west of Rio, on the way to São Paulo – where Hugo managed a farm producing medicinal plant extracts for the Geigy pharmaceutical company.

In early 1943, faced with threats of having their false identity exposed, the couple moved again to the town of Barbacena – four hours north, on the way to Belo Horizonte – where they remained for the duration of the war. There, an unlikely friendship sprang up between Hugo Simon and fellow exile Georges Bernanos, the French nationalist writer. Hugo made a living by raising silkworms and dedicated his time to writing an autobiographical novel, which remained unfinished. It is presently housed, along with many of his papers, in the Exile Archive 1933-1945 of the German National Library.

After the end of the Second World War, Hugo and Gertrud Simon returned to Penedo. From there, they began attempts to reclaim their true identities, as well as their lost properties. Without papers or money, there was no chance of returning to Europe to engage in such efforts directly, so they were obliged to act through intermediaries. Despite the support of prominent friends who vouched for him, among whom Albert Einstein and Thomas Mann, Hugo Simon never managed to recover his name and nationality prior to his death on 4 July 1950. The couple were able to claim back only a very few works of art in France and the ruins of their house in west Berlin, destroyed by bombing. Gertrud Simon continued to live in southern Brazil, where she died in 1964.

That same year, their two daughters and son-in-law began proceedings to regain their German nationality and rectify their names and legal standing, which were successfully concluded in 1972, more than thirty years after their flight from Europe. It would be another two decades before further claims could be initiated for the recovery of Hugo Simon’s properties lost in former East Germany.

Permanent exhibition

The exhibition Hugo Simon: from red banker to green exile, curated by Rafael Cardoso and Anna-Dorothea Ludewig, seeks to reveal the extraordinary life of Hugo Simon through documents and photographs. It consists of five sections: 1) Hugo Simon; 2) People and networks; 3) Berlin Tiergarten; 4) Seelow, Oderbruch; 5) France and Brazil. It was first presented in Berlin, at the Brazilian Embassy, in 2018, and subsequently reinstalled at the Schweizerhaus Seelow in 2019. The exhibition is free and open to the public during regular opening hours or, privately, upon prior request.

Publications

Writings on Hugo Simon:

- Anna-Dorothea Ludewig, Hugo Simon, vom roten Bankier zum grünen Exilanten (Jüdische Miniaturen). Leipzig: Hentrich & Hentrich, 2021.

- Nina Senger, „Werke Ludwig Meidners in der Sammlung Hugo Simon“, in: Expressionismus, Ekstase, Exil. Ludwig Meidner. Hrsg. Erik Riedel und Mirjam Wenzel, Frankfurt a. M., 2018, 129-151.

- Anna-Dorothea Ludewig & Rafael Cardoso (Hrsg.), Hugo Simon in Berlin. Leipzig: Hentrich & Hentrich, 2018.

- Rafael Cardoso, Das Vermächtnis der Seidenraupen. Frankfurt a.M.: S. Fischer, 2016.

- Nina Senger, „Hugo Simon (1880-1950) Bankier - Sammler - Philanthrop“, in: Jüdische Sammler und ihr Beitrag zur Kultur der Moderne. Hrsg. Annette Weber, Heidelberg, 2011, 149-163.

- Marlen Eckl, Das Paradies ist überall verloren: das Brasilienbild von Flüchtlingen des Nationalsozialismus. Frankfurt a.M.: Vervuert, 2010.

- Nina Senger mit J. Th. Köhler, Jan Maruhn, „Utopische Plaudereien. Paul Cassirer und die Architektur“, in: Ein Fest der Künste. Paul Cassirer. Der Kunsthändler als Verleger. Hrsg. Rahel Feilchenfeldt und Thomas Raff, München, 2006, 347-363.

- Nina Senger mit. J. Th. Köhler, Jan Maruhn, Berliner Lebenswelten der zwanziger Jahre. Bilder einer untergegangenen Kultur photographiert von Marta Huth. Katalog herausgegeben zusammen mit dem bauhaus archiv Berlin und der Landesbildstelle Berlin, Frankfurt a. M., 1996.

- Izabela Maria Furtado Kestler, Die Exilliteratur und das Exil der deutschsprachigen Schriftsteller und Publizisten in Brasilien. Frankfurt a.M.: Lang, 1992.

- Maria Eugênia Tollendal, Uma tríade histórica. Barbacena: Gráfica Editora Mantiqueira, 1989.

- Edita Koch, “Hugo Simon/Hubert Studenic”, Exil 1933-1945, 1 (1983), 48-61.

Other related publications:

- Der Hirscheber im Schweizerhaus: eine Geschichte in 159 Scherben. Seelow: Heimatverein Schweizerhaus Seelow, 2021.

- Das Areal Schweizerhaus. Seelow: Heimatverein Schweizerhaus Seelow, 2011.

Hugo Simon art collection: research and restitution

Hugo Simon was a leading art collector in Berlin during the Weimar Republic. His collection, animated by the passion and keen eye of both himself and his wife Gertrud, included works today regarded as masterpieces: the 1895 pastel version of Edvard Munch’s Scream, currently in the Museum of Modern Art in New York; Franz Marc’s Horse in a landscape (1910), in the Folkwang Museum in Essen; Oskar Kokoschka’s Lady in Red (1911), in the Milwaukee Art Museum; among many others currently housed in major museums such as the Art Institute of Chicago, the Belvedere Museum (Vienna), Kunsthaus Zürich, Kunstmuseum Basel, Kunstmuseum Bern, Kunstmuseum Winterthur, Musée d’Orsay (Paris), the Norton Simon Museum (Pasadena). Hugo Simon was also a prominent supporter of the National Gallery in Berlin, active as a donor and member of its acquisitions committee. He maintained close personal ties to the art dealer Paul Cassirer and to numerous artists. His son-in-law, married to the couple’s eldest daughter Ursula, was the sculptor Wolf Demeter.

Among the contemporary artists whose works were represented in the collections of Hugo and Gertrud Simon are Alexander Archipenko, Ernst Barlach, André Derain, Lyonel Feininger, August Gaul, George Grosz, Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Paul Klee, Oskar Kokoschka, Georg Kolbe, Marie Laurencin, Wilhelm Lehmbruck, Max Liebermann, Aristide Maillol, Franz Marc, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Ludwig Meidner, Otto Mueller, Edvard Munch, Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein, Pablo Picasso, Renée Sintenis, Max Slevogt, Kees van Dongen. The Simon couple were also interested in the art of earlier periods, especially the nineteenth century, and owned works by Canaletto, Cézanne, Corot, Courbet, Daumier, Friedrich, Guardi, Leibl, Monet, Pissarro, Poussin, Puvis de Chavannes, Renoir, Tintoretto, Toulouse-Lautrec, van Cleve, van Ruysdael, von Marées, among many others.

After going into exile, Hugo Simon managed to get a substantial portion of the collection out of Germany. Some of the artworks were taken to Paris, where the couple resided between 1933 and 1940. Others were deposited in museums in Switzerland for safekeeping. As conditions of survival grew more desperate, the couple began to sell works, not only to support themselves but also to finance the anti-Nazi struggle as well as relief efforts directed to German refugees, exiled artists and writers. Other works were offered as collateral against credits from the Swiss museums where they were held. Despite the dire situation, Hugo Simon still managed to act as one of the major lenders to the two 1938 exhibitions of Twentieth Century German Art, in London, and L’Art allemand libre, in Paris, curated respectively by Herbert Read and Paul Westheim as responses to the ‘degenerate art’ exhibitions of the preceding year in Germany.

Soon after the invasion of Paris in June 1940, Hugo Simon’s residence and offices were plundered by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR) and the Möbel Aktion, two of the main organizations tasked with looting by the Nazi regime. In October 1941, six crates of objects belonging to him were shipped from the German repository in the Jeu de Paume to Berlin. During the War, they were dispersed, and the whereabouts of many remain unknown to this day. In June 1945, Hugo Simon made the first of a series of claims attempting to recover his lost collection. As a result of investigations carried out by the Allied authorities charged with restitutions, approximately nine works of art were returned to the Simons in 1947 to 1948, among other items of furniture and household goods. The largest part of the collection – as many as 250 works – was not recovered. A few of the properties left behind by the Simons when they fled Paris, including works of art, remained in their former apartment, placed under seal by the German authorities. After 1945, these were confiscated by the Banque de l’Algérie, proprietor of the apartment, and, despite judicial efforts by Hugo Simon until the time of his death, kept by the bank and eventually sold off in the 1960s when it was liquidated.

The heirs of Hugo and Gertrud Simon never gave up their attempts to recover properties lost during the War, including the art collection. Their legal endeavours over the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s were mostly unsuccessful. After the fall of the Berlin Wall and the opening of former East German archives and institutions, a new round of claims was initiated with greater success. The publication of the Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art, in 1998, helped move the public discussion towards the responsibility of museums and collections to facilitate provenance research. Over the past decades, a few important restitution cases have reaffirmed the relevance of Hugo Simon’s many outstanding claims. Wherever possible, the heirs to the estate seek to cooperate with current owners to achieve just and fair solutions. As part of its mission to preserve his legacy, the Hugo Simon Foundation supports the family in their effort to seek reparation and restitution.

Research into the Hugo Simon collection entered a new phase, in 2020 to 2022, with the execution of the project Rekonstruktion der Kunstsammlung des jüdischen Berliner Bankiers Hugo Simon (1880-1950), co-sponsored by the heirs of Hugo Simon and Hamburg University (Kunstgeschichtliches Seminar) and funded by the German Lost Art Foundation (DZK). The initial results of that project hold the promise that the complete reconstruction of Hugo and Gertrud Simon’s unique collection may one day be possible. The new research carried out has already begun to shed light on some of the darker corners of the art world during the Nazi dictatorship and in its aftermath. The list, below, of restitutions and settlements provides an updated inventory of artworks once belonging to Hugo Simon that have been cleared in terms of provenance and ownership. Information on works considered unclear or missing can be found on the DZK’s Lost Art database:

Artworks recovered; with source and date of restitution:

- André Derain, Beauty and the beast; Commission de Récuperation Artistique, 1947

- Emil Orlik, Portrait of a woman [Gertrud Simon]; Commission de Récuperation Artistique, 1947

- Pablo Picasso, Horse (drawing); Commission de Récuperation Artistique, 1947

- Camille Pissarro, pastel drawing of a landscape; Commission de Récuperation Artistique, 1947

- Puvis de Chavannes, Head of a girl, front and profile (two sanguine drawings); Commission de Récuperation Artistique, 1947

- Unidentified author, nineteenth-century portrait of a man; Commission de Récuperation Artistique, 1947

- August Gaul, Ostrich (bronze); Commission de Récuperation Artistique, 1948

- Georg Heinrich Crola, Landschaft mit Eichen (1837); Staatliche Museen zu Berlin/Preußischer Kulturbesitz, 2007

- Rudolf Henneberg, Spazierritt (1861-63); Staatliche Museen zu Berlin/Preußischer Kulturbesitz, 2007

- Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld, Reiterkampf (c.1872); Staatliche Museen zu Berlin/Preußischer Kulturbesitz, 2007

- Max Pechstein, Schneelandschaft (1917); Staatliche Museen zu Berlin/Preußischer Kulturbesitz, 2007

- Otto Mueller, Selbstbildnis (c.1909); York Castle Museum, 2011

- Max Pechstein, Vier Akte in Landschaft (1912); Musée National d’Art Moderne (Centre Georges Pompidou), 2020

- Kees Van Dongen, Deux baigneuses (1912); private collection, 2023

Artworks for which settlements were achieved; with date:

- Lyonel Feininger, Raddampfer (1912); 2011

- Lyonel Feininger, Hafen von Schwinemünde (1915); 2011

- Wilhelm Leibl, Mädchen mit weißem Mullhut (undated); 2016

- Paula Modersohn-Becker, Selbstbildnis mit Tulpen (1907); 2017

- Lyonel Feininger, Alt Salenthin (1912); 2019

- Max Liebermann, Bäuerin auf dem Feld (1878); 2022